Roma.The novel of ancient Rome, стр. 55

“Not anymore! I’m afraid of him now. Ever since Verginia died, he’s a different person. He suffers from the beatings he took from the lictors; one of his eyes will never be the same. There’s so much anger in him, so much bitterness. He never used to hate patricians; now he’s more vengeful than Father ever was. He talks of nothing but harming those he hates. We can’t look to him for help, Titus.”

“But he’ll have to know, sooner or later. The decision will be his to make.”

“Decision?” She was not sure what he meant.

He drew back from her, just enough to reach up and lift the necklace over his head. A bit of sunlight glittered on the golden talisman he called Fascinus.

“For our child,” he said, placing it over her neck.

“But Titus, this belongs to your family. It’s your birthright!”

“Yes, passed from generation to generation, since the beginning of time. The child inside you is mine, Icilia. I give this talisman to my child. The law prevents our marriage. Even if the law allowed it, your brother would forbid it. But no law, no man-not even the gods-can stop us from loving one another. The life inside you is the proof of that. I give Fascinus to you, and you will give it to the child you bear.”

The pendant was cold against her flesh, and surprisingly heavy. Titus had claimed it brought good fortune, but Icilia remembered her doubts.

“Oh, Titus, what’s to become of us?”

“I don’t know. I only know I love you,” he whispered. He thought she meant the two of them, but Icilia was thinking of herself and the helpless life within her. At that moment, she felt the baby stir and give a kick, as if pricked by its mother’s fear.

The midwives, when Lucius angrily consulted them, all agreed: while there existed means by which a pregnancy could be ended-the insertion of a slender willow branch, or the ingestion of the poison called ergot-it was much too late to do so without gravely endangering Icilia herself. Unless he cared nothing for his sister’s life, she must be allowed to bear the child.

The news clearly displeased Lucius. The oldest and most wizened of the midwives, who had witnessed every possible circumstance attending the birth of child, drew him aside. “Calm yourself, Tribune. Once the baby is delivered, it can easily be disposed of. If you wish to save your sister and avoid gossip, this is what I advise…”

Icilia was sent away from Roma, to stay with a relative of the midwife who lived in a fishing camp outside Ostia. There was no need for Lucius to invent excuses for his sister’s absence. A young, unmarried woman had little public life; few people missed Icilia, and those who did readily accepted the explanation that she was in seclusion, still mourning her father.

Icilia’s labor was long and difficult. The ordeal stretched over a day and a night-time for word to reach her brother in Roma, and time for him to arrive in the fishing camp even as the baby was being born.

Afterward, when Icilia came to her senses, the first thing she saw was Lucius standing over her in the darkened room. Her heart leaped with sudden hope. Surely he would not have come all the way from Roma if he simply intended to have the baby drowned in the Tiber, or cast into the sea.

“Brother! I was in such pain…”

He nodded. “I saw the sheets. The blood.”

“The baby-”

“A boy. Strong and healthy.” His voice was flat. It was hard to read any expression on his face. He no longer ever smiled, and the upper lid of his bad eye drooped.

“Please, brother, bring him to me!” Icilia reached up with her arms.

Lucius shook his head. “It’s best if you never see the child again.”

“What are you saying?”

“Titus Potitius came to me a few days ago. He asked me-no, begged me-to allow him to adopt your child. ‘No one need know where it came from,’ he said. ‘I’ll say it was an orphan from the wars, or the child of a distant cousin. I’ve asked my father to let me do this thing, and he gave his permission.’” Lucius shook his head. “I told Titus Potitius, ‘It will still be a bastard.’ ‘That doesn’t matter,’ he said. ‘If it’s a boy, he shall have my name and I shall raise him as my son.’ That’s why I came today, sister.”

“So that you can give the boy to Titus?” Icilia sobbed, partly from relief, partly from sadness.

Lucius grunted. “To the contrary! I told the patrician scum that under no circumstances would he ever come into possession of the child. That’s why I’m here. I feared Potitius might discover your whereabouts and try to lay his hands on the baby. I will make sure that doesn’t happen.”

Icilia clutched his arm. “No, brother-you mustn’t kill him!”

Lucius raised an eyebrow, causing the other to droop even more. “That was my intention. But now that I’ve seen the child, I have an even better idea. I shall take him with me back to Roma, where I shall raise him as a slave, to serve me and my household. Imagine that! A patrician’s bastard, serving as a whipping boy in a plebeian household!” He smiled grimly, pleased at the idea.

“But Lucius, the child is your nephew.”

“No! The child is my slave.”

“And what of me, brother?”

“I know a Greek trader from Croton, at the furthest ends of Magna Graecia. He’s agreed to take you for his wife. You set sail from Ostia tomorrow. You must never speak of the child. You must never return to Roma. Your life will be whatever you make of it. You and I shall not speak again.”

“Lucius! Such cruelty-”

“The Fates are cruel, Icilia. Fortuna is cruel. They robbed me of Verginia-”

“So now you rob me of my child?”

“The child is a bastard and doesn’t deserve to live. This is an act of clemency, sister.”

“Let me see him!”

“No.”

Icilia saw that he would not be swayed. “Do one thing for me, brother. I ask only one thing! Give him this, from me.” With trembling hands, she raised the necklace over her head.

Lucius snatched it from her and studied at it angrily. “What is this? Some sort of talisman? It didn’t come from anyone in our family. Titus Potitius gave it to you, didn’t he?”

“Yes.”

Lucius stared at it for a long moment, then slowly nodded. “Why not? It seems to be made of gold; I could just as easily take it for myself and melt it down for the value, but I’ll do as you ask. I shall let the slave boy have it, as a gaudy trinket to decorate his neck. It will serve to remind me of his origin. Let the ancient bloodline of the Potitii continue in the veins of a slave, and let the slave wear this talisman as a mark of shame!”

THE VESTAL

393 B.C.

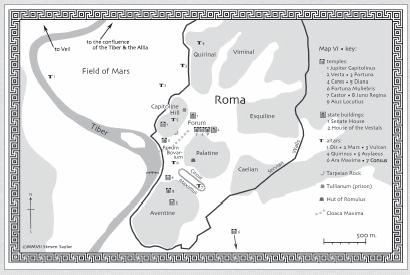

On the eve of the greatest catastrophe yet to befall the city, the unsuspecting people of Roma celebrated their greatest triumph. One of the city’s oldest rivals had at last been vanquished.

The city of Veii was scarcely twenty miles from Roma. A man with strong legs could walk the distance in a single day. A rider on horseback could journey there and back in a matter of hours. Yet, for generation after generation, even as Roma conquered more distant enemies, Veii remained proudly independent, sometimes at peace with Roma, sometimes at war with her. In recent generations, Veii had grown immensely wealthy. Her alliances with other cities in the region began to threaten Roma’s dominance of the salt route and traffic on the Tiber.

For ten summers in a row, Roma’s armies laid siege to Veii, yet with the coming of each winter and the cessation of warfare, Veii remained unconquered. It would take a very great general to put an end to Veii, men said. At last such a general appeared. His name was Marcus Furius Camillus.

No one who witnessed it would ever forget the triumphal parade of Camillus. All agreed that it was by far the grandest triumph in memory; the number of captives, the sheer magnificence of the booty displayed (thanks to the opulence of Veii), and the joyous spirit of the event outstripped all previous triumphs. But, impressive as they were, it was not these details that made the event unforgettable; it was the sight of Camillus in a chariot pulled by four white horses.